Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball

Court of Appeal [1893] 1 QB 256; [1892] EWCA Civ 1

Overview

Facts

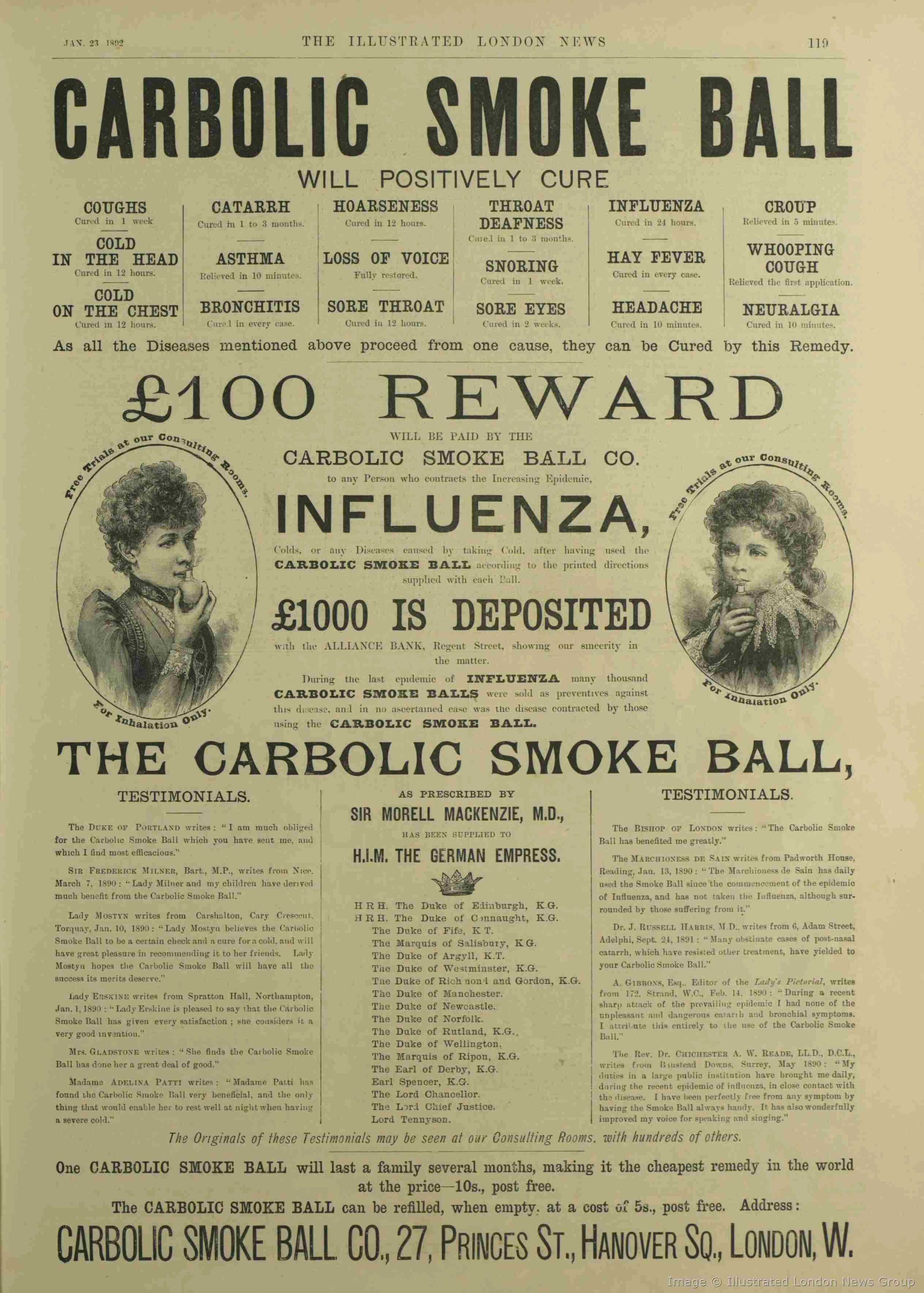

The Carbolic Smoke Ball Co produced the 'Carbolic Smoke Ball' designed to prevent users contracting influenza or similar illnesses. The company's advertised (in part) that:

“100 pounds reward will be paid by the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company to any person who contracts the increasing epidemic influenza, colds, or any disease caused by taking cold, after having used the ball three times daily for two weeks according to the printed directions supplied with each ball. 1,000 pounds is deposited with the Alliance Bank, Regent Street, showing our sincerity in the matter”.

After seeing this advertisement Mrs Carlill bought one of the balls and used it as directed. She subsequently caught the flu and claimed the reward. The company refused to pay. Mrs Carlill sued for the reward.

Held

Mrs Carlill was entitled to the reward. There was a unilateral contract comprising the offer (by advertisement) of the Carbolic Smoke Ball company) and the acceptance (by performance of conditions stated in the offer) by Mrs Carlill.

There was a valid offer

An offer can be made to the world

This was not a mere sales puff (as evidenced, in part, by the statement that the company had deposited £1,000 to demonstrate sincerity)

The language was not too vague to be enforced

Although as a general rule communication of acceptance is required, the offeror may dispense with the need for notification and had done so in this case. Here, it was implicit that the offeree (Mrs Carlill) did not need to communicate an intention to accept; rather acceptance occurred through performance of the requested acts (using the smoke ball)

There was consideration; the inconvenience suffered by Mrs Carlill in using the smokeball as directed was sufficient consideration. In addition, the Carbolic Smoke Ball received a benefit in having people use the smoke ball.

Facts, claims and defence

The Carbolic Smoke Ball Co produced the 'Carbolic Smoke Ball' designed to prevent users contracting influenza or similar illnesses. The company's advertisement for the product read, in part:

“100 pounds reward will be paid by the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company to any person who contracts the increasing epidemic influenza, colds, or any disease caused by taking cold, after having used the ball three times daily for two weeks according to the printed directions supplied with each ball. 1,000 pounds is deposited with the Alliance Bank, Regent Street, showing our sincerity in the matter”.

After seeing this advertisement Mrs Louisa Elizabeth Carlill bought one of the balls and used it as directed, three times a day, from November 20, 1891, to January 17, 1892, when she contracted influenza. She claimed the reward. The company refused to pay, even after receiving letters from her husband, who was a solicitor.

The claim

Mrs Carlill sued, arguing that there was a contract between the parties, based on the company's advertisement and her reliance on it in purchasing and using the Smoke Ball. It was argued:

The advertisement was clearly an offer; it was designed to be read and acted upon and was not an empty boast

The advertisement was made to the public and as soon as a person does the specified act there is a contract

Merely performing the act constitutes acceptance; further communication is not necessary: in particular, it 'never was intended that a person proposing to use the smoke ball should go to the office and obtain a repetition of the statements in the advertisement. ... Where an offer is made to all the world, nothing can be imported beyond the fulfillment of the conditions. Notice before the event cannot be required; the advertisement is an offer made to any person who fulfils the condition ...'

The terms are not too vague and uncertain

It would not matter if Mrs Carlill had not bought the balls directly from the defendant, as an increased sale would constitute a benefit to the defendants even if via a middleman.

On the issue of the absence of a time limitation, it was noted that there were several possible constructions; it may be that 'a fortnight's use will make a person safe for a reasonable time.'

The defence

Carbolic Smoke Ball Co argued there was no binding contract. They argued that, while the words in the advertisement expressed an intention, they did not amount to a promise. They further argued:

the advertisement was too vague to constitute a contract (in particular, it is not time limited and it would not be possible to check whether the ball had been used or used correctly)

there was no consideration from the plaintiff - the terms of the alleged contract would enable someone who stole and used the balls to claim the reward

to make a contract by performing a condition there needs to be either communication of intention to accept the offer or performance of some overt act; in particular, merely performing an act in private is not sufficient

if there was a contract it was a 'wagering' contract (void under statute at the time)

The Trail (Justice Hawkins)

Mrs Carlill was entitled to recover the reward.

The appeal

Lord Justice Lindley

Promise or puff?

Lord Justice Lindley observed that there was an express promise to pay £100 in certain events:

'Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will, here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable -

£100 reward will be paid by the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company to any person who contracts the influenza after having used the ball three times daily for two weeks according to the printed directions supplied with each ball." '

It was not a mere puff; this conclusion was based on the passage in the advertisement stating that £1,000 was deposited with the bank to show sincerity. This could have no other purpose than to negate any suggestion that this was a mere puff.

Was it a binding promise? Is notification of acceptance required?

Noted this advertisement was an offer to pay £100 to anyone who performed the stated conditions, 'and the performance of the conditions is the acceptance of the offer'. On the issue of whether notification of acceptance was required:

Unquestionably, as a general proposition, when an offer is made, it is necessary in order to make a binding contract, not only that it should be accepted, but that the acceptance should be notified.

But cases such as this constitute an exception to this general proposition or,

'if not an exception, they are open to the observation that the notification of the acceptance need not precede the performance. This offer is a continuing offer. It was never revoked, and if notice of acceptance is required - which I doubt very much ... the person who makes the offer gets the notice of acceptance contemporaneously with his notice of the performance of the condition. If he gets notice of the acceptance before his offer is revoked, that in principle is all you want. I, however, think that the true view, in a case of this kind, is that the person who makes the offer shews by his language and from the nature of the transaction that he does not expect and does not require notice of the acceptance apart from notice of the performance.'

Was the advertisement too vague?

His Lordship observed that the language is vague and uncertain in some respects. However, in relation to 'time' for which someone who used the smokeball would be 'protected', his Lordship noted that it was for the defendants to show what it means and he preferred the meaning that 'the reward is offered to any person who contracts the epidemic or other disease within a reasonable time after having used the smoke ball'. He considered that what constituted a 'reasonable time' could be ascertained in a 'sense satisfactory to a lawyer'.

Was there valid consideration?

His Lordship noted the argument that this was a 'nudum pactum' and there was no advantage to the defendants in the use of the ball. His Lordship rejected this argument, stating:

'It is quite obvious that in the view of the advertisers a use by the public of their remedy, if they can only get the public to have confidence enough to use it, will react and produce a sale which is directly beneficial to them. Therefore, the advertisers get out of the use an advantage which is enough to constitute a consideration.'

His Lordship also observed that a person who acted upon this advertisement and accepted the offer, put himself to inconvenience at the request of the defendants. This alone was sufficient to constitute consideration.

Conclusion

His Lordship concluded:

'It appears to me, therefore, that the defendants must perform their promise, and, if they have been so unwary as to expose themselves to a great many actions, so much the worse for them.'

Lord Justice Bowen

His Lordship agreed with Lord Justice Lindley

Vague or ambiguous?

His Lordship noted that the advertisement constituted an offer. On the defendants' contention that the terms of that offer were too vague to constitute an offer - particularly because there was no fixed time limit for catching influenza - his Lordship observed that it was necessary to 'read this advertisement in its plain meaning, as the public would understand it. It was intended to be issued to the public and to be read by the public.' His Lordship considered the advertisement was intended to make people use the smoke ball and interpreted the advertisement as follows:

"£100 will be paid to any person who shall contract the increasing epidemic after having used the carbolic smoke ball three times daily for two weeks."

The public would interpret this as meaning that if, after the advertisement was published, somebody used the carbolic smoke ball three times a day for two weeks and then caught the cold they would be entitled to the reward. His Lordship considered there were two possible time frames within which the claim could be brought, but preferred the construction that the reward would be open while the smoke ball was still being used:

'It may mean that the protection is warranted to last during the epidemic, and it was during the epidemic that the plaintiff contracted the disease. I think, more probably, it means that the smoke ball will be a protection while it is in use. That seems to me the way in which an ordinary person would understand an advertisement about medicine, and about a specific against influenza. ... I, therefore, have myself no hesitation in saying that I think, on the construction of this advertisement, the protection was to endure during the time that the carbolic smoke ball was being used. My brother, the Lord Justice who preceded me, thinks that the contract would be sufficiently definite if you were to read it in the sense that the protection was to be warranted during a reasonable period after use. I have some difficulty myself on that point; but it is not necessary for me to consider it further, because the disease here was contracted during the use of the carbolic smoke ball.'

Mere puff?

His Lordship agreed that this was not a mere puff, for the same reasons as Lord Justice Lindley - the deposit in the bank showing sincerity. In relation to the argument that 'it would be an insensate thing' to promise such sums to persons unless it was possible to check their manner of using it, his Lordship stated:

'The answer to that argument seems to me to be that if a person chooses to make extravagant promises of this kind he probably does so because it pays him to make them, and, if he has made them, the extravagance of the promises is no reason in law why he should not be bound by them.'

Offer to the world

In response to the defendant's argument that this was a 'contract with the world' and it was not possible to make a contract with the world, his Lordship stated:

'It is not a contract made with all the world. There is the fallacy of the argument. It is an offer made to all the world; and why should not an offer be made to all the world which is to ripen into a contract with anybody who comes forward and performs the condition? It is an offer to become liable to any one who, before it is retracted, performs the condition, and, although the offer is made to the world, the contract is made with that limited portion of the public who come forward and perform the condition on the faith of the advertisement.'

On the issue of notification of acceptance

As had Lord Justice Lindley, Lord Justice Bowen observed that:

'as an ordinary rule of law, an acceptance of an offer made ought to be notified to the person who makes the offer, in order that the two minds may come together. Unless this is done the two minds may be apart, and there is not that consensus which is necessary according to the English law ... to make a contract.'

Bowen LJ noted, however, that 'notification of acceptance is required for the benefit of the person who makes the offer' and that person 'may dispense with notice to himself if he thinks it desirable to do so'. If the person making the offer 'expressly or impliedly intimates in his offer that it will be sufficient to act on the proposal without communicating acceptance of it to himself, performance of the condition is a sufficient acceptance without notification.' In advertisement cases:

'it seems to me to follow as an inference to be drawn from the transaction itself that a person is not to notify his acceptance of the offer before he performs the condition, but that if he performs the condition notification is dispensed with. It seems to me that from the point of view of common sense no other idea could be entertained. If I advertise to the world that my dog is lost, and that anybody who brings the dog to a particular place will be paid some money, are all the police or other persons whose business it is to find lost dogs to be expected to sit down and write me a note saying that they have accepted my proposal? Why, of course, they at once look after the dog, and as soon as they find the dog they have performed the condition. The essence of the transaction is that the dog should be found, and it is not necessary under such circumstances, as it seems to me, that in order to make the contract binding there should be any notification of acceptance. It follows from the nature of the thing that the performance of the condition is sufficient acceptance without the notification of it, and a person who makes an offer in an advertisement of that kind makes an offer which must be read by the light of that common sense reflection. He does, therefore, in his offer impliedly indicate that he does not require notification of the acceptance of the offer.'

On the issue of consideration

In relation to the argument that this was a 'nudum pactum' his Lordship observed that in this case there had been a 'request to use' involved in the offer and a person reading the advertisement who 'applies thrice daily, for such time as may seem to him tolerable, the carbolic smoke ball to his nostrils for a whole fortnight' suffered an inconvenience sufficient to create a consideration. As a result, his Lordship concluded that by using the smokeball as directed, Mrs Carlill had provided consideration. In addition (although this was not essential), the defendants received a benefit because 'the use of the smoke balls would promote their sale.'

Lord Justice AL Smith

His Lordship agreed with Lord Justice Lindley

Vague or ambiguous?

His Lordship noted that the advertisement constituted an offer. On the defendants' contention that the terms of that offer were too vague to constitute an offer - particularly because there was no fixed time limit for catching influenza - his Lordship observed that it was necessary to 'read this advertisement in its plain meaning, as the public would understand it. It was intended to be issued to the public and to be read by the public.' His Lordship considered the advertisement was intended to make people use the smoke ball and interpreted the advertisement as follows:

"£100 will be paid to any person who shall contract the increasing epidemic after having used the carbolic smoke ball three times daily for two weeks."

The public would interpret this as meaning that if, after the advertisement was published, somebody used the carbolic smoke ball three times a day for two weeks and then caught the cold they would be entitled to the reward. His Lordship considered there were two possible time frames within which the claim could be brought, but preferred the construction that the reward would be open while the smoke ball was still being used:

'It may mean that the protection is warranted to last during the epidemic, and it was during the epidemic that the plaintiff contracted the disease. I think, more probably, it means that the smoke ball will be a protection while it is in use. That seems to me the way in which an ordinary person would understand an advertisement about medicine, and about a specific against influenza. ... I, therefore, have myself no hesitation in saying that I think, on the construction of this advertisement, the protection was to endure during the time that the carbolic smoke ball was being used. My brother, the Lord Justice who preceded me, thinks that the contract would be sufficiently definite if you were to read it in the sense that the protection was to be warranted during a reasonable period after use. I have some difficulty myself on that point; but it is not necessary for me to consider it further, because the disease here was contracted during the use of the carbolic smoke ball.'

Mere puff?

His Lordship agreed that this was not a mere puff, for the same reasons as Lord Justice Lindley - the deposit in the bank showing sincerity. In relation to the argument that 'it would be an insensate thing' to promise such sums to persons unless it was possible to check their manner of using it, his Lordship stated:

'The answer to that argument seems to me to be that if a person chooses to make extravagant promises of this kind he probably does so because it pays him to make them, and, if he has made them, the extravagance of the promises is no reason in law why he should not be bound by them.'

Offer to the world

In response to the defendant's argument that this was a 'contract with the world' and it was not possible to make a contract with the world, his Lordship stated:

'It is not a contract made with all the world. There is the fallacy of the argument. It is an offer made to all the world; and why should not an offer be made to all the world which is to ripen into a contract with anybody who comes forward and performs the condition? It is an offer to become liable to any one who, before it is retracted, performs the condition, and, although the offer is made to the world, the contract is made with that limited portion of the public who come forward and perform the condition on the faith of the advertisement.'

On the issue of notification of acceptance

As had Lord Justice Lindley, Lord Justice Bowen observed that:

'as an ordinary rule of law, an acceptance of an offer made ought to be notified to the person who makes the offer, in order that the two minds may come together. Unless this is done the two minds may be apart, and there is not that consensus which is necessary according to the English law ... to make a contract.'

Bowen LJ noted, however, that 'notification of acceptance is required for the benefit of the person who makes the offer' and that person 'may dispense with notice to himself if he thinks it desirable to do so'. If the person making the offer 'expressly or impliedly intimates in his offer that it will be sufficient to act on the proposal without communicating acceptance of it to himself, performance of the condition is a sufficient acceptance without notification.' In advertisement cases:

'it seems to me to follow as an inference to be drawn from the transaction itself that a person is not to notify his acceptance of the offer before he performs the condition, but that if he performs the condition notification is dispensed with. It seems to me that from the point of view of common sense no other idea could be entertained. If I advertise to the world that my dog is lost, and that anybody who brings the dog to a particular place will be paid some money, are all the police or other persons whose business it is to find lost dogs to be expected to sit down and write me a note saying that they have accepted my proposal? Why, of course, they at once look after the dog, and as soon as they find the dog they have performed the condition. The essence of the transaction is that the dog should be found, and it is not necessary under such circumstances, as it seems to me, that in order to make the contract binding there should be any notification of acceptance. It follows from the nature of the thing that the performance of the condition is sufficient acceptance without the notification of it, and a person who makes an offer in an advertisement of that kind makes an offer which must be read by the light of that common sense reflection. He does, therefore, in his offer impliedly indicate that he does not require notification of the acceptance of the offer.'

On the issue of consideration

In relation to the argument that this was a 'nudum pactum' his Lordship observed that in this case there had been a 'request to use' involved in the offer and a person reading the advertisement who 'applies thrice daily, for such time as may seem to him tolerable, the carbolic smoke ball to his nostrils for a whole fortnight' suffered an inconvenience sufficient to create a consideration. As a result, his Lordship concluded that by using the smokeball as directed, Mrs Carlill had provided consideration. In addition (although this was not essential), the defendants received a benefit because 'the use of the smoke balls would promote their sale.'

'One is the consideration of the inconvenience of having to use this carbolic smoke ball for two weeks three times a day; and the other more important consideration is the money gain likely to accrue to the defendants by the enhanced sale of the smoke balls, by reason of the plaintiff's user of them. There is ample consideration to support this promise.'

Trivia

Mrs Carlill died in 1942 at the age of 96. Her death certificate stated that she died of influenza! (see: Clive Coleman, 'Carbolic smoke ball: fake or cure?' (BBC Radio 4, 5 November 2009))

Further resources

Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball

Video summary by Phillip Taylor on YouTube (4min summary)

Professor Stephan Graw on Carlill

(at the 2012 ALTA Conference) (1min)

The Carlill case has inspired many law student parodies ...

Mrs Carlil and her Carbolic Smokeball Capers

YouTube video by Adam Javes

Carlill v Carbolic Smokeball Company: The Movie

YouTube video by Davey G

Carlill v Carbolic Smokeball

YouTube video by peterjcgoodchild